Christopher Columbus

Best known as: Italian explorer and navigator

Born: 1451 in Genoa, Italy

Died: May 20, 1506 in Valladolid, Spain

Resting place: Seville, Spain / Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Alternative names: Cristoforo Colombo (Italian), Cristobal Colon (Spanish)

Biography:

The origins of Christopher Columbus are somewhat mysterious. His birthday is not known, but most scholars agree that he was born between August 25 and October 31, 1451 in the Republic of Genoa, part of what is now Italy. His father, Domenico Colombo, was a wool-weaver and a cheesemaker. His mother's name was Susanna Fontanarossa, and he had four siblings: Giovanni, Giacomo, Bartolomeo, and Bianchinetta. Growing up, Christopher worked at the family cheese stand and was fascinated by the sea from a young age.

Christopher first went to sea at age 10. He worked a variety of different jobs during his teens and twenties, including as a business agent for several prominent families of Genoa and a mercenary in the service of Rene of Anjou in his attempt to conquer Naples. In 1476 as part of a convoy that carried valuable cargo from Genoa to Northern Europe, he visited Bristol, England and Galway, Ireland. From 1477 to 1485, Columbus lived in Lisbon, Portugal and worked as a merchant and mapmaker. He also traveled to West Africa during this time, going as far south as Ghana. Intellectually curious and eager to rise up the social ladder, Columbus taught himself about history, geography, and astronomy and learned Spanish, Portuguese, and Latin. He married a Portuguese noblewoman named Filipa Moniz Perestrelo in 1479, and they had a son named Diego.

Sadly, Filippa died in the early 1480s and Christoper and Diego moved to Castile, part of what is now Spain, in 1485. In 1487 he met a new girlfriend, Beatriz Enriquez de Arana. They had a son named Fernando, although they never ended up marrying. Around this time, Columbus got the idea of finding a westward route to Asia. This was motivated, at least in part, by the fact that the silk road had been closed to Christian travelers since 1452, when the Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople. As a result, since Columbus's childhood, Europeans did not have easy access to goods such as spices and silk that they had enjoyed before. Although most people of Columbus's time knew that the world was round, sailing west from Europe to Asia was considered too far and dangerous of a journey to be practicable.

Columbus needed financial support in order to carry out his idea, and he submitted proposals to the rulers of Portugal, Genoa, Venice, and Spain. He was unsuccessful each time. King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, however, decided to give him a modest yearly allowance, perhaps to keep him from taking his ideas elsewhere. In January 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella conquered Granada, thereby taking back the Iberian Peninsula from Muslin control. They decided to give Columbus's idea a try after all. They arrived at an agreement that if Columbus succeeded, he would receive the rank of Admiral of the Ocean Sea, would be appointed Viceroy and Governor of any lands he discovered, and would be entitled to 10% of all revenues from the new lands.

On August 3, 1492 Columbus left from Palos de la Frontera with three ships. The largest was called the Santa Maria, and the other two were nicknamed the Nina and the Pinta, although their official names are not known. The owner and captain of the Santa Maria was named Juan de la Cosa, and the captains of the Nina and Pinta were brothers Martin and Vicente Pinzon. Columbus and his crew made a pit stop at the Canary Islands and continued west. Columbus kept two logs tracking how far they had traveled: one showing the true distance and one showing a shorter distance, which he showed to his crew. At one point, the crew wanted to turn back, and threatened to mutiny and throw him overboard. To pacify his crew, Columbus promised to turn back if land was not sighted within two days, but in his journal he wrote that he had no intention of doing so.

In the early morning of October 12, a lookout on the Pinta sighted land. Upon reaching the shore, Columbus interacted amicably with the natives and managed to communicate with them using signs. He described them as intelligent, although primitive in terms of technology and military matters. He named the island San Salvador ("Holy Savior") and called the natives Indians, believing the island to be part of Asia. The island was actually in what is now the Bahamas. Columbus also explored Cuba and Hispaniola and encountered the Lucayan, Taino, and Arawak people during his first voyage. On Christmas Day, the Santa Maria ran aground. Columbus left 39 men behind on Hispaniola, founding a settlement called La Navidad ("Christmas") with the permission of the local chief, Guacanagari. Wood from the Santa Maria was used to build the settlement. Meanwhile, Martin Pinzon had gone off on his own with the Pinta in search of gold. With only the Nina, Columbus continued sailing along the coast of Hispaniola. He eventually met up with Pinzon again and encountered another group of natives called the Ciguayos, with whom he and his men had a small battle. Because of this skirmish, Columbus called this inlet in Hispaniola the Bay of Arrows.

After a couple of storms and a stop in Portugal, Columbus returned home to Spain on March 15, 1493. Cheering crowds lined the streets. Ferdinand and Isabella were delighted with what he had accomplished, and he soon became famous throughout Europe.

That September, he set out again on a second expedition to the New World, which he and most people still believed to be part of Asia. This time, he had a fleet of 17 ships carrying 1,200 people and numerous supplies with which to establish permanent settlements. Pursuant to his agreement with the king and queen, his job was to serve as Governor of Hispaniola and the surrounding islands. Columbus discovered and named numerous islands during this voyage, including Dominica, Guadalupe, Montserrat, Antigua, Nevis, Saint Kitts, Saint Eustatius, Saint Martin, Saint Croix, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico (he originally named it San Juan Bautista, a name that was later given to its capital city). On Saint Croix, Columbus and his men encountered and had a skirmish with a group of natives called the Caribs. On Puerto Rico, they rescued some women whom another group of Caribs were holding captive as sex slaves, as well as some boys whom the Caribs were planning to eat. Next, Columbus visited Hispaniola, only to find that all 39 of the men at La Navidad had been killed. He founded a new settlement, in another part of Hispaniola, called La Isabela. Columbus remained in the New World from 1493 to 1496, serving as governor. In 1494, his brothers Giacomo and Bartolomeo arrived at Hispaniola to help him rule. Accounts differ on his treatment of the native people and the settlers and exactly what policies he implemented. He has received a lot of criticism for alleged brutality towards the natives, but some accounts state that settlers abused natives against Columbus's wishes and that he was powerless to stop them, and some people at the time actually criticized him for being too harsh towards settlers who abused the natives.

Columbus returned to Spain in 1496 and made another voyage to the New World in May of 1498. He had six ships, three of which brought supplies to Hispaniola, and three of which he took on an expedition south of the islands he had previously explored. Hoping to find the mainland of Asia, Columbus instead sighted Trinidad and continued on to what is now Venezuela. One of his men planted a Spanish flag there but Columbus, not feeling well, opted not to go ashore. He and his small fleet continued on to Margarita, Tobago, and Grenada. Then he returned to Hispaniola, where both European settlers and natives were openly rebelling. He sent two ships back to Spain in 1499 to ask the king and queen for help. But people had already complained to them, alleging that Columbus was an incompetent and cruel governor. Ferdinand and Isabella sent Francisco de Bobadilla to investigate these allegations. In October of 1500, he arrested Columbus and his brothers Giacomo and Bartolomeo and sent them back to Spain in chains. After six weeks in jail, Columbus was summoned before the king and queen. He successfully persuaded them to acquit and free him, but he had permanently lost his job as governor.

Although he was getting older and his health was declining, Columbus still wanted to make one more voyage to the New World. Ferdinand and Isabella agreed to fund a fourth voyage, although they forbade Columbus from setting foot on Hispaniola. His objective was to find the Strait of Malacca, a passage to the Indian Ocean. He had a fleet of four ships and was accompanied by his brother Bartolomeo and his son Fernando. He left Spain in May of 1502, made a pit stop in Morocco to rescue some Portuguese soldiers, and then sailed on to the Caribbean, making stops at Martinique and several other islands. Sensing that a hurricane was brewing, he attempted to warn the new governor of Hispaniola, Nicolas de Ovando, but Ovando ignored him and didn't let him land. While Columbus's ships took shelter nearby, a large Spanish fleet sailed into the storm and was destroyed (his nemesis, Bobadilla, was aboard and was killed). Next, Columbus explored the coasts of what are now Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica and sighted the Cayman Islands, which he named Las Tortugas ("Turtles"). During these travels, his ships sustained damage from various storms, from attacks by native people, from shipworms, and in one instance from getting stuck in a river. He and his men became stranded in Jamaica in June of 1503, where they remained for a year. Columbus used his wits and knowledge of astronomy to convince the natives to help him. He knew that a lunar eclipse was going to occur on February 29, 1504 and told the local leaders that unless they provided his men with food, God would turn the moon red as a sign of his anger. Sure enough, the eclipse happened, the intimidated natives brought provisions, and when the eclipse ended Columbus told them that God had forgiven them. Eventually, ships from Spain finally came to rescue Columbus and his men, and he returned home in 1504.

Columbus lived out his remaining years in Valladolid, Spain. His health was failing, most likely due to either gout or reactive arthritis, and he was disappointed and bitter about the way he had been treated. He petitioned the king and queen to restore his titles and give him a share of the revenues from the New World as they had initially promised, but because he had been fired from his job as governor, they did not feel bound to hold up their end of the bargain. Columbus also still believed that the lands he had discovered were part of Asia, despite the fact that most people were beginning to realize they were part of a new continent. He became increasingly religious and increasingly eccentric as he got older. In his last few years, he wrote two books: the Book of Privileges and the Book of Prophecies. He died peacefully, with his two sons and two brothers by his side, on May 20, 1506.

The travels of Columbus did not end with his death, however. He was initially buried in a convent in Valladolid, then moved to a monastery in Seville. But he had wanted to be buried in the New World, so after the death of his son Diego in 1526, both their bodies were moved to Hispaniola, specifically to Santo Domingo in what is currently the Dominican Republic. In 1796, Hispaniola became part of France, so the remains were sent to Havana, Cuba. But after Cuba gained its independence in 1898, the remains were sent back to Seville, where they were placed in an elaborate tomb in the Seville Cathedral. Making matters even more complicated, in 1877 a box was discovered in Santo Domingo marked "Christopher Columbus," with the bones of an arm and a leg inside. These bones were placed in an elaborate tomb in the Columbus Lighthouse in 1992. It is possible that both sets of bones are authentic: perhaps Columbus's remains were split up at some point, with half going to Cuba and then Seville and half remaining in Santo Domingo.

Physical characteristics:

Because there were no portraits painted of Columbus during his lifetime, no one knows exactly what he looked like. He is said to have been tall and in excellent shape, with reddish or blond hair and blue eyes. Paintings depict him with a variety of hair colors ranging from black to brown to white, both with a beard and without.

Personality:

Columbus was very ambitious, self-confident, brave, and determined. Although he did not have much formal education, he was extremely intelligent and intellectually curious. He loved to read and taught himself about the topics he was interested in, which included astronomy, geography, languages, and history. He seems to have been very opinionated and independent-minded, with strong ideas that, although not always right, he stuck to in the face of opposition and adversity. Many people found him quirky and eccentric. His son, Fernando, described him as patient, forgiving, loyal, and with a pleasant, although serious, demeanor. Although he proved not to be a great governor, it's hard to dispute that he was a gifted navigator and courageous man. He was very religious, especially as he got older, and some accounts say that he never even swore.

Fun facts:

- He believed that the earth was pear-shaped, with the northern, pointed end extending upwards to heaven. (The earth actually is very slightly pear-shaped.)

- On his first voyage, he brought pineapples and turkeys to Europe for the first time.

- On his second voyage, he brought horses to the New World.

- His son, Fernando, dedicated his life to collecting all the books in the world.

Quotes:

- "By prevailing over all obstacles and distractions, one may unfailingly arrive at his chosen goal or destination."

- "Nothing that results in human progress is achieved with unanimous consent. Those that are enlightened before the others are condemned to pursue that light in spite of the others."

- "Goals are simply tools to focus your energy in positive directions, these can be changed as your priorities change, new ones added, and others dropped."

- "Riches don't make a man rich, they only make him busier."

- "Life has more imagination than we carry in our dreams."

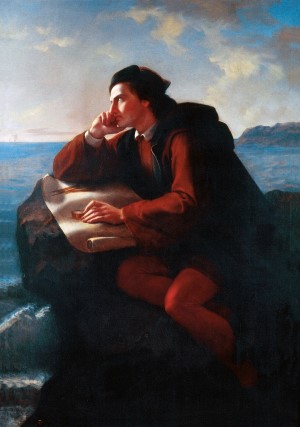

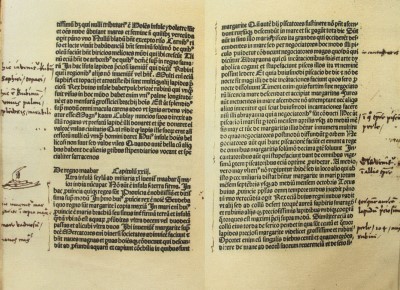

Pictures:

Portrait of a Man, Said to be Christopher Columbus, by Sebastiano del Piombo, 1519. This is the best-known image of Columbus, but it was not painted during his lifetime, and there is dispute about whether or not it actually depicts Columbus.

Columbus portrait by Currier & Ives, 1892

The Inspiration of Christopher Columbus by Jose Maria Obregon, 1856

Christopher Columbus at the gates of the monastery of Santa Maria de la Rabida with his son Diego, by Benito Mercade y Fabregas, 1858

Columbus explaining his idea to Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand

Columbus bidding farewell to Queen Isabella as he embarks on his first voyage, by Prang Educational Co., 1893

Columbus's Arrival by Dióscoro Teófilo Puebla Tolín, 1862

Columbus's coat of arms (via Library of Congress)

Columbus's signature

Columbus's copy of the Travels of Marco Polo, with his handwritten notes

Links:

- Columbus Monuments Pages

- Columbus Monument Syracuse

- ColumbusTheTruth.org

- Columbus's Ultimate Goal: Jerusalem - paper by anthropologist Carol Delaney

- Italian American Alliance

- Knights of Columbus page about their namesake

- Know Columbus

- Official Christopher Columbus

- Sons & Daughters of Italy - Columbus Day Page

- Truth About Columbus

- We the Italians - Columbus section